Introduction

A wine glass slips from your hand, shattering into a thousand pieces on the floor. An ice cube in your drink slowly melts into a formless puddle. We watch ourselves and those around us grow older, never younger. This is the arrow of time—a fundamental, irreversible, and deeply intuitive feature of existence.

But here’s the puzzle: the fundamental laws of physics that govern the universe, from the motion of planets to the dance of subatomic particles, don’t seem to care about the direction of time. Their equations work just as well forwards as they do backwards. So, what enforces this strict, unwavering, forward-only march that we experience as time? The answer doesn’t lie in clocks or calendars, but in one of the most powerful and misunderstood concepts in all of science: entropy.

But what is Entropy?

At its heart, entropy is a measure of disorder, or more accurately, probability. Thinking back to our shattered wine glass, there is essentially only one way for all those glass molecules to be arranged in a crystalline structure to form a perfect wine glass—a state of low entropy, or high order. But there are countless, astronomically numerous ways for those same pieces to be scattered across the floor in a broken heap—a state of high entropy, or high disorder. The universe, on a grand statistical level, simply favors states that are more probable. It’s not that the shattered pieces can’t spontaneously reassemble themselves, but the odds are so infinitesimally small that we would have to wait trillions of times longer than the age of the universe to see it happen therefore allowing us to classify it as practically impossible. This is the core of the fundamental principle of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which dictates that the total entropy of an isolated system will always increase over time. This relentless increase in disorder is the engine that drives time’s arrow forward.

But why are the probabilities lower for disorder than order?

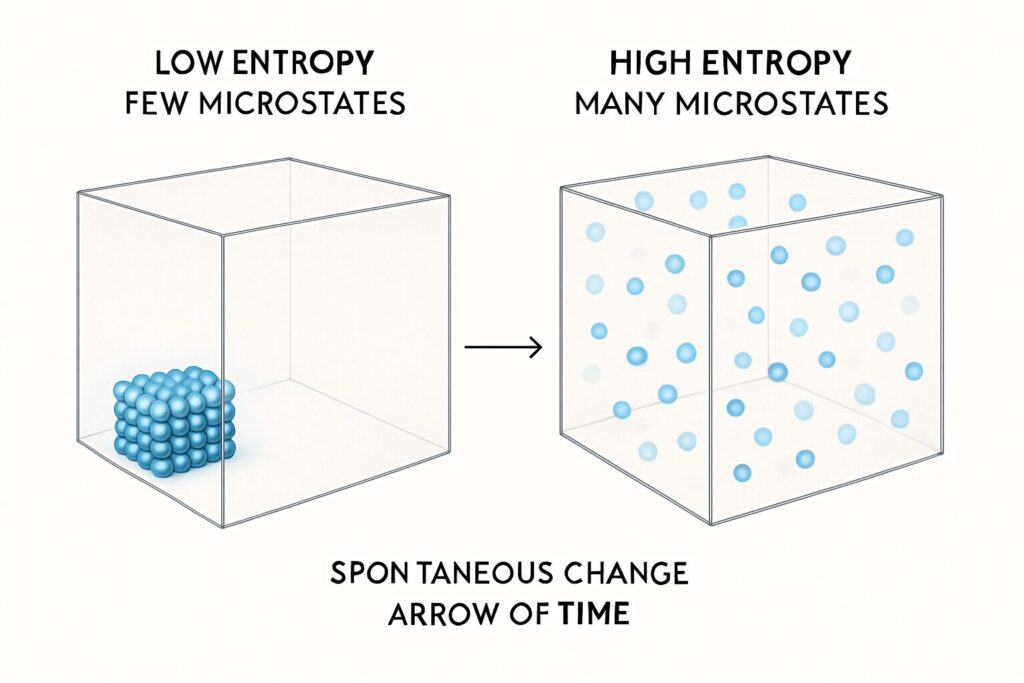

Picture a box containing just ten molecules, like a tiny puff of air. Let’s say we start them all neatly arranged in one corner—a state of perfect order. If we wait a moment, they will naturally spread out to fill the entire box. Why? It’s not because of a mysterious “disordering force.” It’s simply a matter of counting the possibilities. The state of “all ten molecules in the left corner” represents just one possible arrangement. The state of “all ten molecules spread throughout the box,” however, can be achieved in a staggeringly vast number of different ways.

Physicists call each of these specific arrangement of particles a microstate. The ordered condition—all molecules in the corner—corresponds to a very small number of microstates. But the disordered condition—the molecules being generally spread out—corresponds to an astronomical number of available microstates. Swapping the positions of just two molecules creates a brand new microstate, yet to our eyes, the box still looks “disordered” in the same way. The system isn’t seeking chaos; it’s simply exploring all its possible configurations, and the vast majority of those configurations happen to look messy and spread out to human perception.

Now, let’s scale this up from ten molecules to the real world. Our shattered wine glass is made of trillions upon trillions of atoms. The number of microstates corresponding to the “whole glass” macrostate is, like our box, incredibly small. All the silicon and oxygen atoms must be locked in a precise crystal lattice. But the number of microstates corresponding to the “shattered glass” macrostate is so colossally larger that the word “larger” fails to capture the scale. There are countless ways the pieces can be oriented, scattered, and resting on the floor. The universe doesn’t forbid the glass from reassembling; it’s just that the odds of the atoms spontaneously finding their way back into one of the few “whole glass” arrangements are, as Feynman would say, fantastically, ludicrously and laughably improbable.

This statistical certainty is the engine of time. A system will always evolve toward the macrostate that contains the most microstates, simply because that state is the most probable. The universe began in a state of remarkably low entropy—a highly ordered, hot, dense state at the Big Bang. From that initial, improbable condition, it has been unfolding into progressively more probable and higher-entropy states ever since. Stars burn, galaxies disperse, and ice cubes melt not because of a directed force, but because they are following the overwhelming odds. The forward arrow of time is, in essence, the universe’s relentless and statistically unavoidable walk from a few ways of being to a multitude of ways of being.

But Can We Defy the Arrow of Time?

At this point, we might be thinking of exceptions that seem to challenge this rule. After all, we can take a puddle of water—a disordered collection of molecules—and put it in a freezer to create a highly ordered ice cube. A skilled craftsperson can gather scattered wood shavings and glue them into a beautiful sculpture. Most profoundly, life itself takes simple molecules and organizes them into complex structures like a tree, a bird, or a human being. Aren’t these examples of time’s arrow being reversed, of order being created from chaos?

The answer is a fascinating and crucial “no,” and it hinges on a single, critical condition of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: it applies to the total entropy of an isolated system. An isolated system is one that doesn’t exchange any energy or matter with its surroundings. A freezer, however, is not an isolated system. To create the ordered ice cube, it must run a powerful compressor and pump, consuming electrical energy and radiating waste heat out of its coils into your kitchen. This process is messy and inefficient. The disorder created by the power plant burning fuel to generate that electricity, combined with the waste heat dumped into your home, is far greater than the small amount of order created inside the ice cube tray and therefore total entropy has increased.

This principle is most magnificently demonstrated by life itself. An organism is a masterpiece of local order, a walking, breathing defiance of chaos. But it is not a closed system. To maintain its intricate structure, an animal must consume ordered, high-energy molecules (food) and in return, it releases disordered, low-energy waste (heat, carbon dioxide). A plant builds its ordered form by absorbing highly concentrated energy from the sun, a process that contributes to the sun’s own slow, inexorable march toward thermodynamic equilibrium. Life doesn’t violate the Second Law; it is a temporary and beautiful eddy in a cosmic river that flows unstoppably toward higher entropy.

So, while we can build temporary dams of order, we can never reverse the river’s flow. Every act of creation, every moment of life, is paid for with a greater contribution to the universe’s total disorder. You can meticulously clean your room (decreasing its entropy), but the energy you burn, the heat you radiate, and the food you metabolized to do so increases the total entropy of the universe by a much larger amount. The universe keeps a perfect ledger, and on the grand scale, the balance always, and irrevocably, tips toward chaos. This is why time, for all of us, can only move forward.

The inevitable end of the universe

The arrow of time, driven by entropy, points toward an ultimate conclusion. The current age of stars will end as the last red dwarfs flicker out. The universe will then fall into a silent, dark Degenerate Era, a cosmic graveyard populated by the cold corpses of stars: neutron stars, black holes, and countless white dwarfs that have cooled over eons into invisible black dwarfs.

But the story has one final, bizarre chapter. On timescales beyond comprehension, quantum tunneling will allow the nuclei inside the most massive of these black dwarfs to slowly fuse, transmuting the dead star into a sphere of pure iron. This transformation is unstable. It triggers a catastrophic collapse and a final, brilliant supernova—the last firework in a dark cosmos.

After that last flash, the universe will settle into its final state of “heat death.” It will be a cold, uniform void of maximum entropy. With no more potential for change or increasing disorder, the very arrow of time will lose its meaning, having finally reached the end of the road.