Introduction

Understanding why light bends or slows when it enters a new material (due to its different refractive index) is a common question in physics classes. However, it’s surprisingly tricky to explain satisfyingly using only introductory concepts. This very challenge sparked my fascination with light and prompted me to delve deeper into how it interacts with the media it travels through.

A Few Common (and not so physically sound) Explanations…

To begin, we will examine some commonly taught models for explaining the laws of refraction, and then demonstrate why these models are physically incorrect.

Absorption and Remission

A common idea you might hear, even from some teachers, to explain why light appears to slow down when the photons travel from one medium to the next is that the photons in the ray are absorbed by the atoms in the medium. After a brief moment, these atoms then eject the photons back out, in a slightly different direction. This constant absorption and reemission cycle, in combination with the indirect path the photons take, give the light the emergent property of travelling at different speeds in different mediums.

However, this idea doesn’t quite hold up physically (as I myself realised while learning). If photons were truly absorbed and then re-emitted in random directions, then water wouldn’t be transparent as the light would be scattered in all directions making the water appear cloudy or opaque which is not what we see in the real world.

Tank Track Model

Another common way teachers attempt to expalin refraction is with the “tank tracks” model. This analogy explains that when light moves from one medium to another, it slows down and changes direction. Like a tank going from pavement to mud: when one of its tracks enters a more optically dense boundary first, that track slows, causing the entire tank to gradually turn and slow. A more detailed diagram used by the BBC can be found here.

This explanation proved extremely unsatisfactory to me for one simple reason - a single photon is simply not a tank and does not have tracks and yet a single photon still refracts despite not having two tracks. It is rare that a simple classical model can be used to satisfactorily explain quantum phenomena. Indeed this is not the case here.

Below I will explore the underlying reasons why light changes speed in a medium, why the change in speed depends on the frequency of the light, why light changes direction during refraction and an explanation of the principle of least action.

Why does light slow down in a medium?

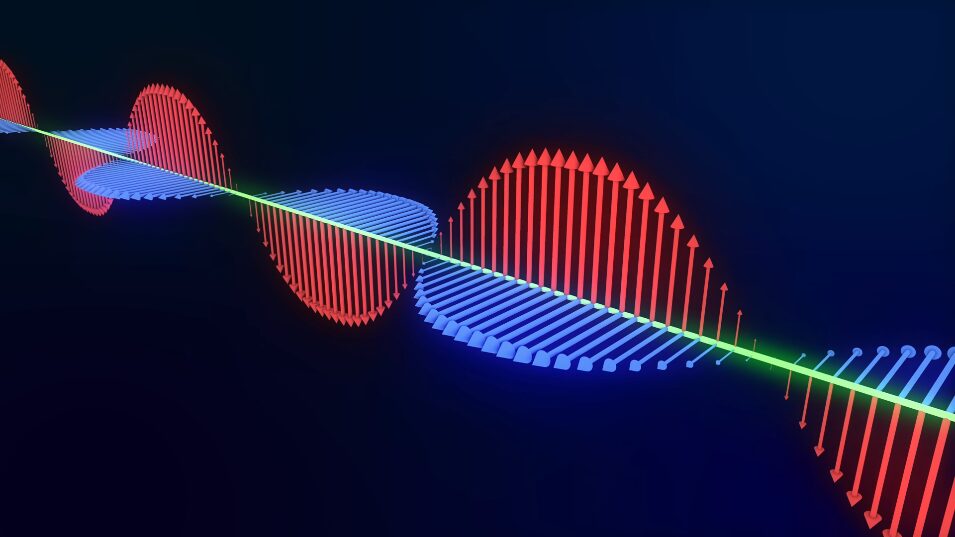

The apparent slowing of light when passing through a medium can be understood by considering the interaction of light, as an electromagnetic wave, with the charged particles within the material, primarily electrons. Light, composed of photons, is characterised by oscillating perpendicular electric and magnetic fields.

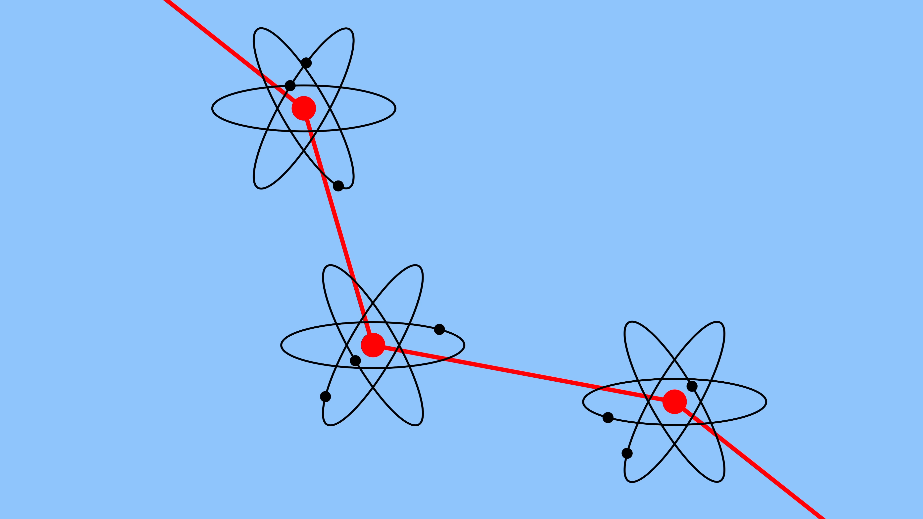

As this incident electromagnetic field propagates through the material, its oscillating electric component exerts a force on the electrons, causing them to oscillate. These oscillating electrons, in turn, become sources of secondary electromagnetic waves of the same frequency as the incident light.

These secondary waves are coherent with the incident light. While the precise phase relationship can be complex and depend on the material and frequency, they are generally out of phase by π/2, the electrons interfere (or superpose) with the original incident wave. In the forward direction of propagation, this superposition generally results in a combined wave whose phase is behind compared to what it would be if the light were propagating in a vacuum over the same distance.

Although the phase shift resulting from interaction with a single layer of atoms is very small, light interacts with numerous layers of atoms as it traverses the material. The cumulative effect of these continuous interactions and the resulting phase retardation of the total electromagnetic field leads to a wave with a shorter wavelength within the medium for the same frequency. Since wave speed is the product of frequency and wavelength (v=fλ), this reduction in wavelength at a constant frequency means the overall wave propagates at a reduced phase velocity. This results in a wave within the material that appears to be a wave of light that is effectively slowed down in a medium.

While this answers many question it raises just as many. Why do different colour of light have different refractive indexes? Why does light bend and not simply travel in a straight line?

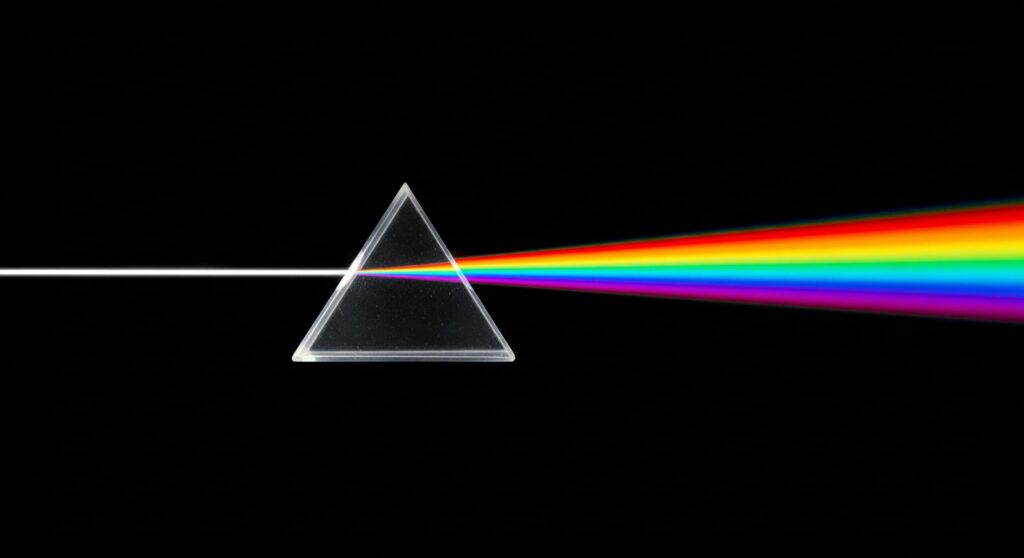

Why do different colours of light have different refractive indicies?

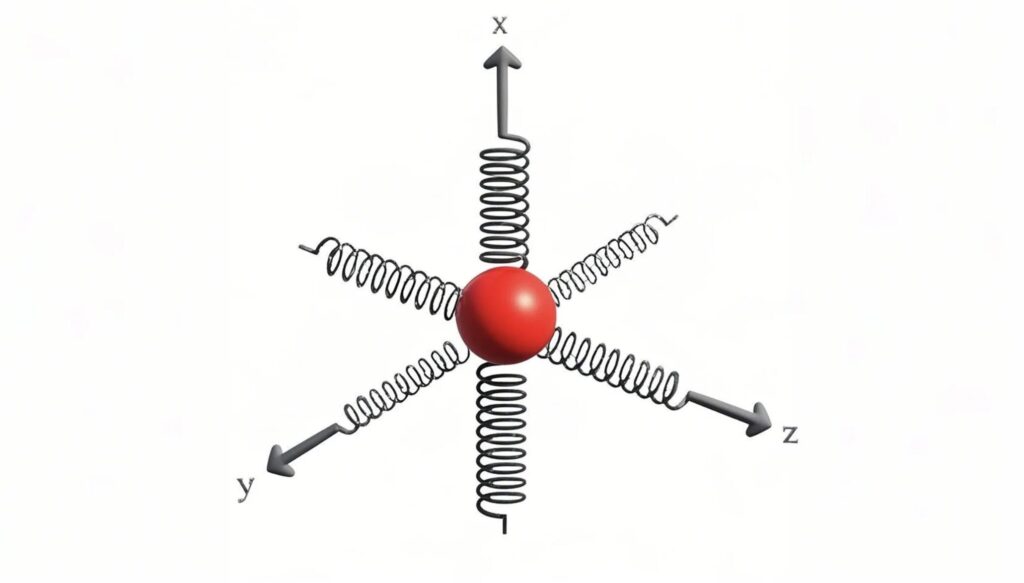

The variation of the refractive index with the colour (or frequency) of light, a phenomenon known as dispersion, is directly linked to the way light interacts with electrons in a medium, as described in the previous paragraph. Electrons within a material have natural (or resonant) frequencies at which they oscillate most readily. These resonant frequencies are intrinsic properties of the material, determined by the electromagnetic binding forces on the electrons (much like a driven harmonic oscillator), giving them a resonant frequency at which they responds most strongly.

Lorentz harmonic oscillator model: Incoming light makes the elastically bound (spring-like) electron oscillate and then “bounce back’ re-emitting its own light

As the frequency of the incident light approaches these material-specific resonant frequencies, the electrons can absorb energy from the light wave more effectively. This increased energy absorption causes electrons to oscillate with significantly larger amplitude, which in turn shifts their phase relationship: the precise timing of their motion relative to the light’s oscillating electric field. Both these changes in the electron’s oscillation (amplitude and phase) significantly alter the characteristics of the secondary electromagnetic waves they re-radiate.

When frequencies of light approaching a material’s resonant frequency, the phase and amplitude of the re-radiated waves relative to the incident wave leads to a greater phase lag in the resulting superposed wave. A larger phase lag means the overall wave is effectively “slowed” more significantly. Therefore, the closer the frequency of the incident light is to the electron’s resonant frequency, the greater the amplitude and phase change of the secondary wave and therefore, the more substantial the slowing effect, and thus, the higher the refractive index.

This explains why, for example, blue light (which has a higher frequency than red light) refracts more than red light when passing through glass. The resonant frequencies for electrons in glass are in the ultraviolet (UV) range. Since blue light’s frequency is closer to the frequency of ultraviolet light than red light’s frequency, it interacts in a way that produces a greater phase lag and, consequently, experiences a higher refractive index and more pronounced bending.

Why does light bend?

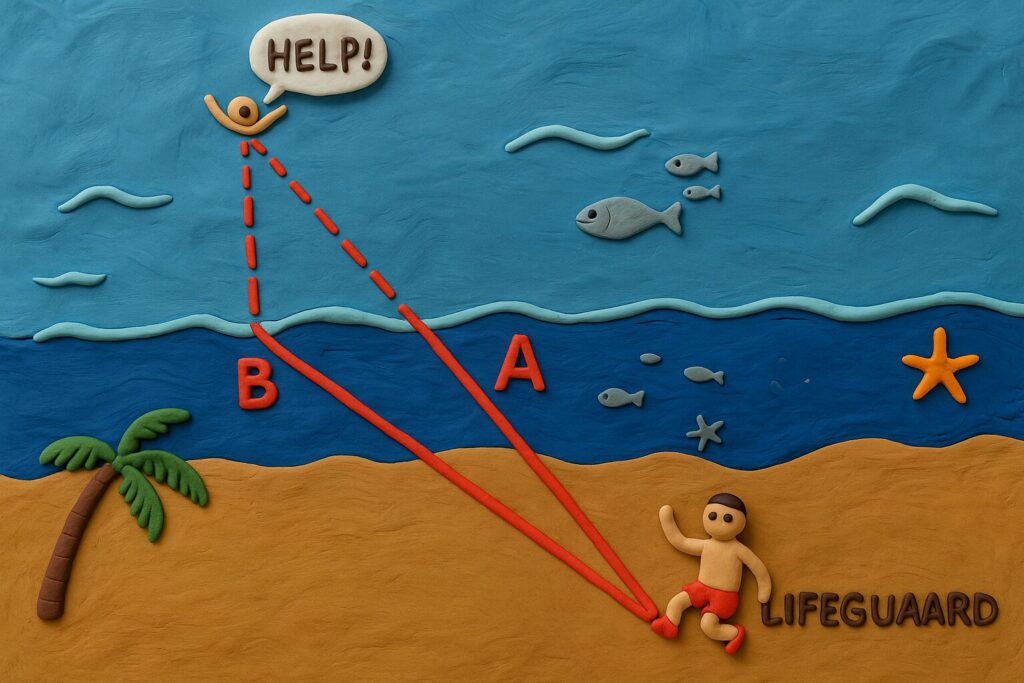

The fastest path for the lifeguard to reach the person lies somewhere between A and B

Now that we have established exactly why light slows down in a medium, we need to explore what causes the change in direction as described by Snell’s Law. To try to find out the reasoning behind why this is the case I turned to 3Blue1Brown’s excellent video on the topic here, however I found this explanation unsatisfactory as it could not explain why a single photon will still undergo refraction and felt analogous to the previous tank explanation.

To resolve this quandary I turned to Fermat’s principle of least time, which states that when light travels between two points it takes the path of least time not necessarily the shortest distance which explains why light bends and its adherence to Snell’s law - which can be simplified to light finding the most time efficient path to get from one point to another. However, simply stating that light bends in order to minimise the travel time is an incomplete explanation and does not explain why light takes the path of least time or how light even knows what the fastest path is, to offer no explanation to these phenomena would leave the important part of physics - the question “why”? - incomplete.

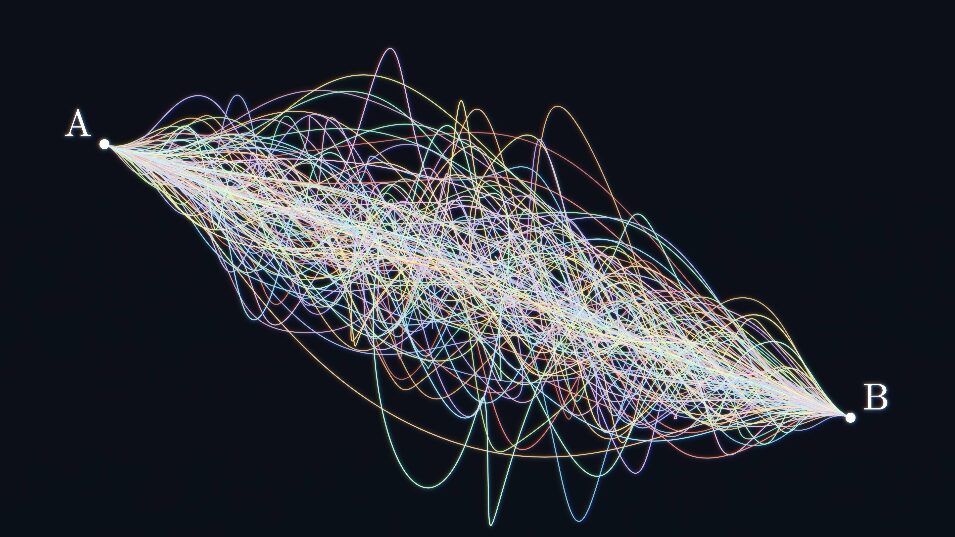

The fascinating reason light adheres to Fermat’s principle isn’t because individual photons are somehow clairvoyant, pre-calculating the quickest route. The deeper answer, which gets to the heart of this “why” and “how,” comes from Richard Feynman’s quantum “sum over paths” (or path integral) formulation. This theory suggests that a photon doesn’t just pick one neat line to get from point A to point B. Instead, it explores every conceivable path simultaneously. One can imagine infinite possibilities, some straight, some looping the photon considers them all.

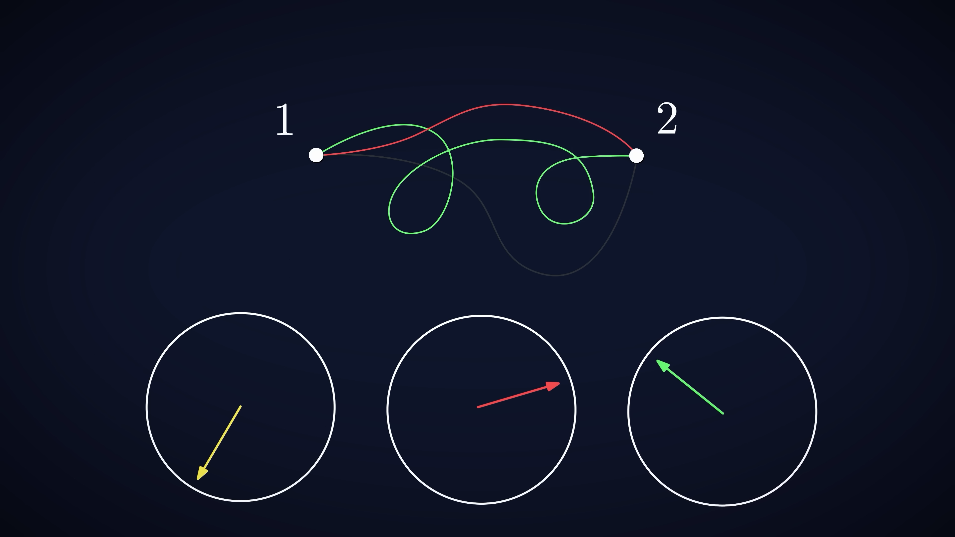

Position of arrows represents the phase

Each of these potential paths that light might explore between two points has a value associated with it, often visualised as a little spinning arrow, with the direction of this arrow determining its phase. The final orientation of this arrow for each path is determined by the total “action” accumulated along that path, divided by Planck’s constant. For light, this action is directly related to the travel time.

The next question we must ask is: how does this flurry of infinite paths, each with its own arrow, result in the single, well-behaved path of least time that is actually observed?

For most imaginable paths, particularly those deviating significantly from the quickest route, their associated ‘arrows’ end up pointing in seemingly random directions. This high sensitivity occurs because the phase, which dictates each arrow’s final orientation, varies greatly even with slight changes to the path. A path’s ‘action’ value is typically so large compared to Planck’s constant that the arrow’s final direction becomes acutely dependent on the precise path taken. Due to this randomness in their final orientations, when the contributions from these numerous paths are combined, they effectively cancel each other out. This is destructive interference; these ‘inefficient’ paths are eliminated as their differently pointing arrows result in a superposition effectively of zero.

At the parabola’s minimum (or least action), the curve is nearly flat. This illustrates that small sideways steps (variations) near the minimum result in very little change in height (action), unlike on the steeper slopes where the same step causes a much larger change

Conversely, for paths very close to the path of least time, the situation is different. For this path and its immediate neighbors, a slight variation in the path geometry results in almost no difference to the total travel time and thus action. This is due to the mathematical nature of an extremum, where the value is ‘flat’ around such a point. Consequently, the arrows for these nearby paths all end up pointing in almost exactly the same direction. Instead of cancelling, their contributions add up and reinforce each other. This is constructive interference, leading to a significant final amplitude.

Therefore, it is this strong, coherent contribution from paths clustered around the path of least time that overwhelmingly dominates. All other paths, with their widely varying phases, have effectively cancelled themselves out. The principle of least time thus emerges not as a prescribed rule, but as the natural consequence of this wave-like interference across all possibilities.

All images used on this page are used under the Free Use Act falling under both the education/research catagory, many thanks to Veritasium, 3Blue1Brown and Fermilab for visuals