Fermi problems are a unique type of challenge that set out to do one thing: answer the unanswerable. By using logic and estimated sums, you can approximate the value to questions which would be either impossible or unfeasible to measure. It’s precisely this intriguing nature that led me to take them up as a fun excercise to test my application of physics.

Fermi, a renowned physicist, would pose such problems to his students to teach them the power of estimation and logical reasoning. For the piano tuner problem, he wouldn’t expect anyone to know the exact figure. Instead, he would guide them to break down the large, seemingly intractable question into a series of smaller, more manageable estimations. This involved considering factors such as:

-

The population of Chicago: A reasonable estimate for the city’s population at the time.

-

The average number of people per household: To estimate the number of households.

-

The percentage of households that own a piano: A guess based on general observation.

-

How often a piano needs tuning: Perhaps once a year, or every few years.

-

How long it takes a piano tuner to tune one piano: A few hours, for example.

-

The number of hours a piano tuner works in a year: Standard working days and hours.

By multiplying and dividing these estimated quantities, one could arrive at a surprisingly close approximation. While the exact figure isn’t the point, the process of logical breakdown and estimation is. Fermi himself, known for his quick calculations, reportedly arrived at an estimate in the low hundreds, demonstrating that even without precise data, a reasonable answer can be found through structured thinking.

Personally I have found the value of fermi problems to be the application of what I am taught in school to real-life problems, which solidifies the concepts and allows me to see the utility of what we have been taught, tying concepts together. Fermi problems also often encourage out-of-the-box thinking which is particularly important for the tougher a level physics problems, physics olympiads (which I recieved Gold in) and various other problems I come across online. These unique problems allow for a further final benefit and that is that they are simply a lot of fun to solve!

Below are some of my favourite fermi problems that I’ve created, completed and verified.

What is total kinetic energy of all the rivers in the world in one year assuming no friction?

-

We need to work out total amount of rainfall on land as this is what provides water to rivers. This can be done by using the estimate that an average of 1000mm (1m) of rain fall on land each year.

-

We must then work out the volume of this water which can be done by finding the surface area of the earth from its approximate radius using the equation 4πr². Which gives (4 × π × (6400 × 10 ³) ² × 1) = 5.15 × 10 ¹⁴

-

We now work out the total mass of all the water that falls on earth by multiplying by the density of water which is 1000 kg for every meter cubed giving us 5.15 × 10 ¹⁷ kg, which we then multiply by 0.3 as only 30% of the earth is land giving us a value of 1.55 × 10 ¹⁷ kg

-

We are now going to make some assumptions on the effeciency of the transfer of water to the rivers as not all water will travel the full distance. Water can be lost to many ways through evaporation, being absorbed by plants, used in resevoirs (that don’t feed back into the sea), agriculture and more. We assume that this is what happens to 60% of water.

-

However we can not discount this water fully as it will still have some kinetic energy therefore we will simply half its value assuming that on average it will travel half as far as its counterparts. This makes our multiplier: (60/2 + 40 = 70% = 0.7). 0.7 x 1.55 × 10 ¹⁷ kg = 1× 10 ¹⁷ kg

-

We now assume that to reach the sea the water must fall an average of 840m (using average hieght above sea level). Using GPE = mgh we get the energy to be 840 × 9.81 × 1 × 10 ¹⁷ = 8.24 × 10 ¹⁹

-

As in the question no kinetic energy is lost we can assume that all the GPE is converted into kinetic energy at some point. This means there must be approximately 8.24 × 10 ¹⁹ joules of energy in our rivers! This is equal to approximately 1/7 of all of humanity’s energy consumption or 390 of the most powerful bombs ever detonated.

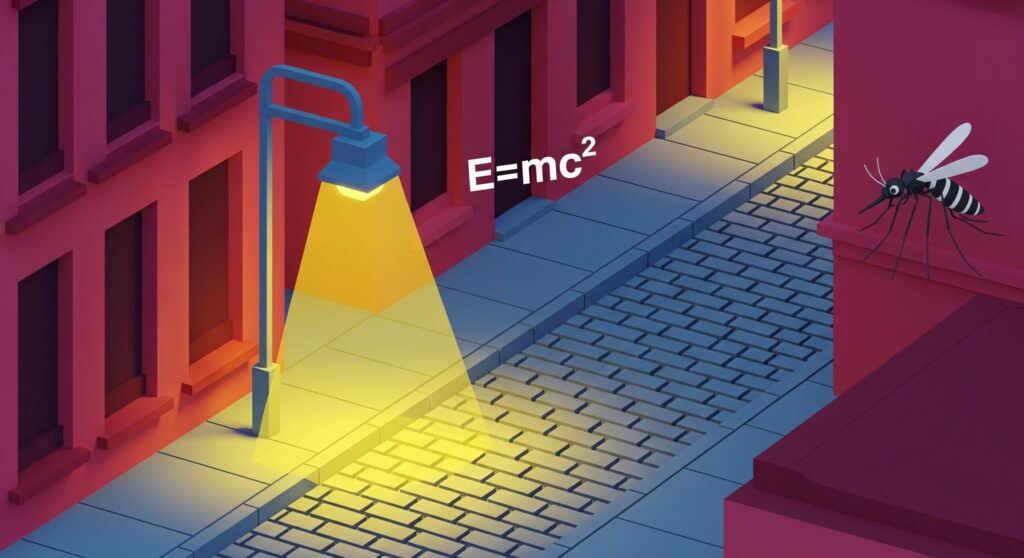

How many photons are emmitted in one night by all the Lamp posts in London?

-

We need to first estimate the total number of streetlamps in London. Which we can do by estimating the total length of roads in London as 15,000 km.

-

Then by using an estimate that since london is a relatively built up city 70% of these roads will be lined with streetlamps with an average spacing of 30m apart, we can arrive at the number of 350,000 lamp posts. 0.7 × 15,000 × 1000 / 30 = 350,000 lamp posts.

-

Now we need to estimate the number of lumens of the average lamp post then convert to photons, the average lamp post is around 15,000 lumens in the UK multiplying that by the conversion factor 1.12 × 10¹⁶ photons per lumen. 1.12 × 10¹⁶ × 15,000 = 1.68×10²⁰ photons per lamp post per second.

-

Now we need to estimate the period where it is dark enough for a lamp post to turn on using the annual burning hours of 4000 hours we get 4000/365 or 11 hours a night. 11 hours = 11 × 3600 = 39,600 seconds.

-

Now we work out total photon emitted by one of the lamp posts in a night by multiplying 39,600 seconds by 1.68×10²⁰ to get 6.65 × 10²⁴ photons in one night.

-

Finally we multiply by the number of streetlights by thier average lumen output to get: 6.65 × 10²⁴ × 350,000 = 2.33 × 10³⁰ photons in one night.

-

This astronomical value if converted into energy (using green light for simplicity) would be equal to only the mass of a single large mosquito, or in other words each night in london our streetlights output enough energy in the form of light to create a mosquito by nuclear fusion.