Shadows of Stewartby

Introduction

This photographic series explores Stewartby, a notable name in Britain’s industrial past, now a landscape of extensive and quiet structures. These images offer a journey into what was once the world’s largest brickworks, focusing on the compelling character of its disused state and the inherent strength of its large, weathered forms. Here, one encounters a distinct atmosphere, where visible traces of a bustling history meet a pervasive and settled quiet, inviting a deeper appreciation for the site’s enduring legacy and unique visual narrative

Factory Foundation and Growth

The London Brick Company was established in 1889 during Britain’s Industrial Revolution by John Cathles Hill, a developer-architect based in Fletton, Huntingdonshire. Hill’s identified the extensive Oxford Clay deposits across Bedfordshire as a prime resource for mass-producing Fletton bricks and a promising economic opportunity. Through strategic acquisitions of land and existing brickyards in the early 20th century, the company was able to rapidly scale up its operations and the 1923 merger with B.J. Forder & Son, led by the influential Stewart family, solidified the company’s dominant position in the Fletton brick market. The merger also initiated the planned expansion of Stewartby as a dedicated company town reminiscent of Victorian Quaker-built towns following a paternalistic model providing comprehensive infrastructure for its workforce, encompassing housing, educational institutions, and recreational facilities

Peak Production Era

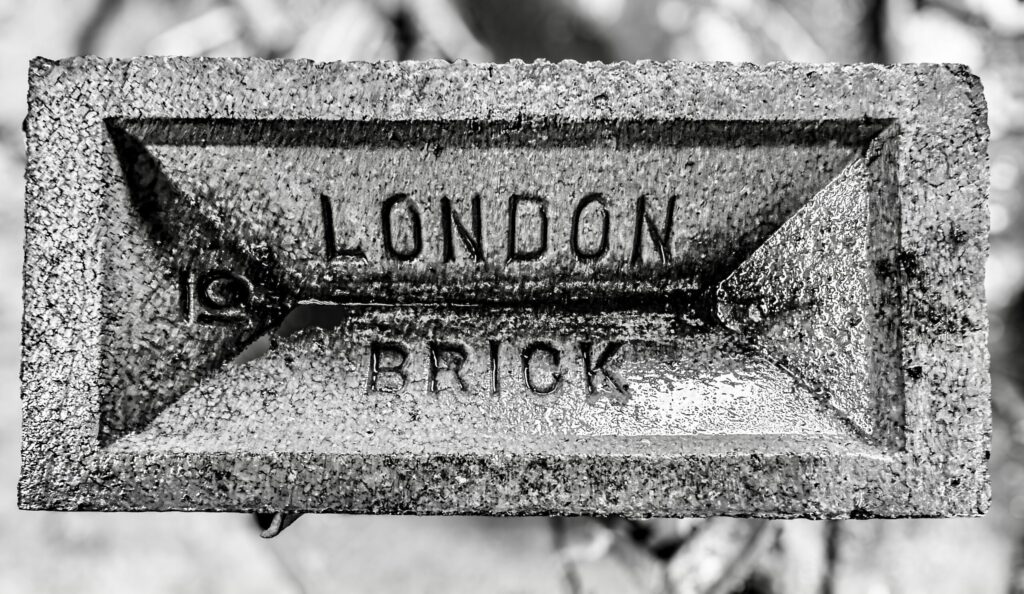

Stewartby Brickworks soon became an emblem of the British industrial capability, its skyline defined by the towering 90-metre chimneys. By 1936, the site had reached its operational peak, becoming recognised as the largest brick factory in the world. Employing over 2,000 individuals, it achieved an annual production of 500 million bricks, supplying enough bricks to build 60,000 homes a year. Fletton bricks, manufactured from the unique Oxford Clay from the are, were renowned for their consistent quality, affordability (thanks to reduced fuel costs during the firing process) and distinct yellowish-brown hue, a direct result of the clay’s high carbonaceous content.

The London brick company also pioneered the use of large-scale dragline excavators and housed the world’s largest continuous kilns, further revolutionising brick manufacturing and establishing its power in the brick industry. These bricks became fundamental to UK construction, utilised in projects ranging from Buckingham Palace, the British Museum and Battersea Power Station to repairing countless homes and industrial buildings in the aftermath of the Second World War. By the 1970s, Bedfordshire, largely due to Stewartby’s output, contributed 20% of England’s total brick production, playing a pivotal role in the national economy and becoming synonymous with the term “London Brick” itself which despite the factory’s closure just under two decades ago still remains synonymous with the company to this day.

End of an Era

During the latter half of the twentieth century, the factory began to face significant challenges. Changes in construction techniques and increasingly stringent environmental regulations led to a decline in demand for the traditional London bricks. Despite considerable financial investment in emissions reduction technologies, exceeding £1 million between 2005 and 2007, Stewartby Brickworks ultimately ceased operations in 2008. The slow downfall and eventual closure of the brickworks triggered a stark decline in the town’s fortunes, exemplified by the population decrease from over 1600 in 1951 to 1100 by 2011, causing economic hardship and loss of identity. However, in recent years the population of Stewartsby has signicantly increased to over 2500 and combined with ambitious proposals for the land such as a Universal studios theme park and mixed use development the town is showing signs of recovery. However, the future of the site still remain shrouded in uncertainty with no concrete plans or developments having been put forward.

Industrial Remants

While the story of Stewartby is a tragic one in its decades of decay the site has slowly been retaken by nature, and now attracts photographers who come to document the industrial husk. Below are some of these elements.

Looming in the dim light of the old factory floor, these immense industrial lines of hoppers tell a silent, powerful story. Their cavernous, funnel-shaped bodies were once the crucial starting point for billions of bricks. They meticulously guided and fed tons of the famed Oxford clay into the roaring heart of production. Now, their still, imposing presence—serves as a relic of its relentless industrial past, embodying the sheer scale of operations and the foundational labour that once defined this historic site.

Suspended under the vast, lattice-work roof of one of the warehouses, a prominent yellow gantry crane cuts a stark line through the diffused light. Once tirelessly traversing the warehouse floor, lifting and positioning heavy bundles of brick central to production, it now hangs motionless—a silent, weighty testament to the bustling activity and formidable power that have long since faded into shadow and memory.

Within Stewartby’s main building, the scale of former operations is palpable, even in decay. This cavernous hall, once echoing with the sounds of relentless production, now holds a profound stillness howling in the wind, its remaining structures bearing witness to the sheer volume of bricks that passed through.

An office frozen in the quiet aftermath of Stewartby’s operational days. Light from the large window illuminates peeling paint and the scattered remnants of work on a forgotten desk. Here, amidst the silence, linger the faint shadows of countless decisions, daily routines, and the human efforts that once managed the might of this brick-making giant.