History

Browne’s Folly Mine, nestled near Bathford in Somerset, England, stands as a captivating relic of the region’s rich quarrying heritage. This mine was once part of an extensive network dedicated to extracting Bath stone—a creamy, oolitic limestone highly prized during the 18th and 19th centuries for its workability and aesthetic appeal. This stone significantly contributed to the construction of Bath’s grand Georgian architecture, imparting the city with its characteristic golden hue that led to it attaining the status of “World Heritage City”. Iconic structures such as the Royal Crescent and the Circus owe their splendor to materials sourced from quarries like Browne’s Folly.

In the 19th century, at the zenith of quarrying activity, workers carved an intricate labyrinth of tunnels into the hillsides, creating chambers and passages that formed the heart of the Bath stone industry providing stone for the entire nation. However, the 20th century brought a decline in demand due to the advent of cheaper building materials such as concrete and brick, leading to the gradual abandonment of quarries which Browne’s Folly was unable to escape. Nature has gradually began to reclaim these sites, transforming the mine into a haven for endangered species such as the greater horseshoe bat.

However, this was not yet the end of the road for the mines. During the second world war, the mine was revived and repurposed to aid with the war efforts along with many of the other Somerset quarries (like the rathe infamous spring quarry). Their natural subterranean environments offered

a safe location for the Ministry of Defence to store ammunition, weapons, and other military supplies away from the prying eyes of the German bombers, protected under metres of thick Bath stone.

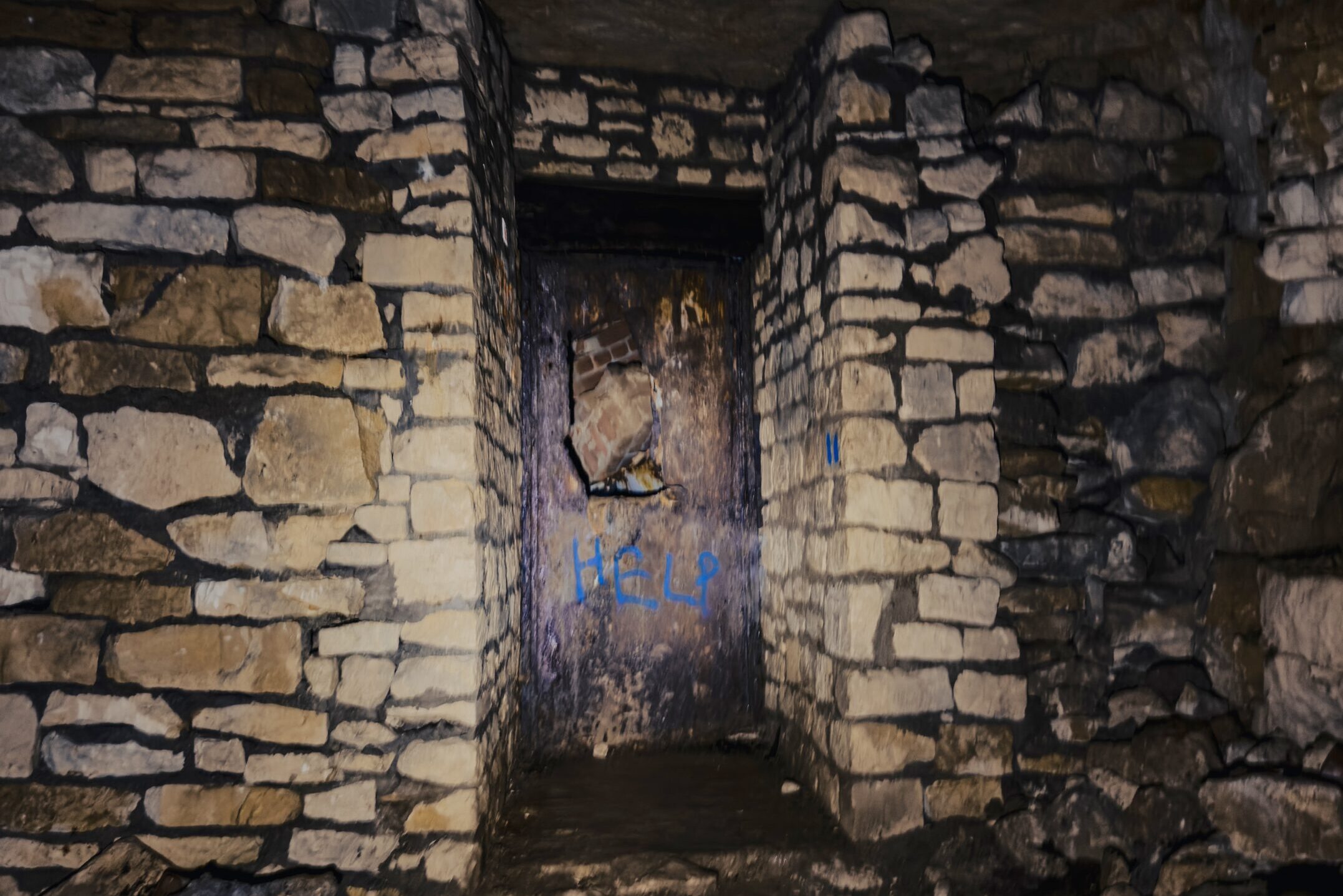

The infamous red door, on the other side lays the natural archives

After the war with the government recognising the value of such an underground space part of the Monkton Farleigh mine was eventually used to house important records from the National Archives, due to it’s stable temperature and humidity levels making it perfect for preserving valuable documents

Making a return back to nature once again the site has now been classified as a site of special scientific interest (SSSI), due to the rare Horeshoe bat that inhabits the mines.

Setting out on a caving expedition to explore these ancient sites, I set off with a couple of friends to explore the system, which I had previously descended into on numerous other equations. Note the photographs are limited in quality due to the poor lighting conditions within the mine and the restriction to phone photography - I wisely decided that bringing expensive fragile equipment into a dusty, wet and tight environment was not the best idea.

These timeworn tracks, disappearing into the shadowy depths of the mine, are more than just rusted iron; they were the arteries of the quarry’s subterranean transport network. Laid through the carved passages hundreds of years ago, this narrow-gauge railway formed a dedicated highway for the minecarts laden with heavy, freshly cut stone or loads of waste rock. By providing a smooth, guided path, these rails dramatically eased the immense effort of hauling multi-tonne burdens, allowing for a more systematic and efficient flow of materials from the working face towards the surface. Today, their silent presence paints a vivid picture of the organized industry and relentless activity that once defined these now-quiet tunnels.

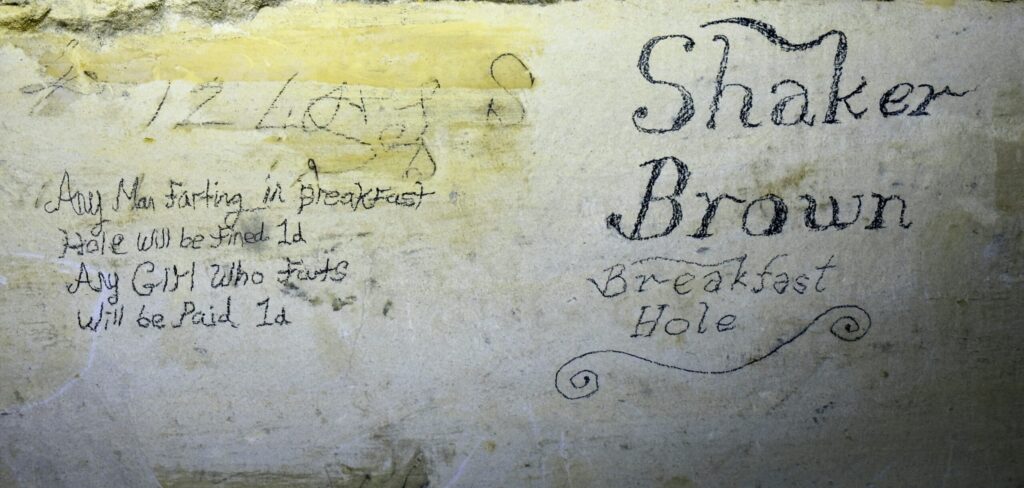

Original miner graffiti, likely dating from the 19th century or early 20th century. Miner’s often used graffit as a form of self expression and protest against the government or directors of the mine, explaining the profanities used in the poem. This is further indicated by the contrast in treatment of the “man” compared to the “girl” suggesting that in the miner’s eyes “girls” have it easier as they would not be expected to toil in the mine for measily pay of “1d”.

This space, identifiable as a loading bay, served as a crucial junction in the mine’s intricate web of subterranean logistics. Here, amidst the dim light and constant toil, quarried stone—freshly hewn from the working faces—would be consolidated and prepared for its journey out of the depths. It was often a bustling point of transfer, where smaller trolleys or even manual efforts might bring stone to be skillfully maneuvered onto larger minecarts waiting on the main haulage tracks. The specific design of such bays, perhaps with varying levels or reinforced edges, aimed to facilitate this demanding work, ensuring a more organized and efficient throughput of material. What remains today is a quiet alcove, yet it echoes with the methodical efforts that kept the heart of the quarry beating, a vital link in the chain from extraction to the world above.

Within these subterranean workings, such a well or sump would have played a key role in the daily operations of the mine. Its primary purpose was efficient dewatering, essential for managing the constant ingress of groundwater and rainwater that is inherent with structures below the water line . This pit would have collected such water, which would then be pumped either through manual horse pumps or steam pumps for larger operations, keeping the working areas clear and safe for stone extraction. Beyond this vital drainage, the accumulated water would also serve other operational needs, such as reducing airborne limestone dust or providing water for stone-cutting work common in an 18th or 19th-century mine.

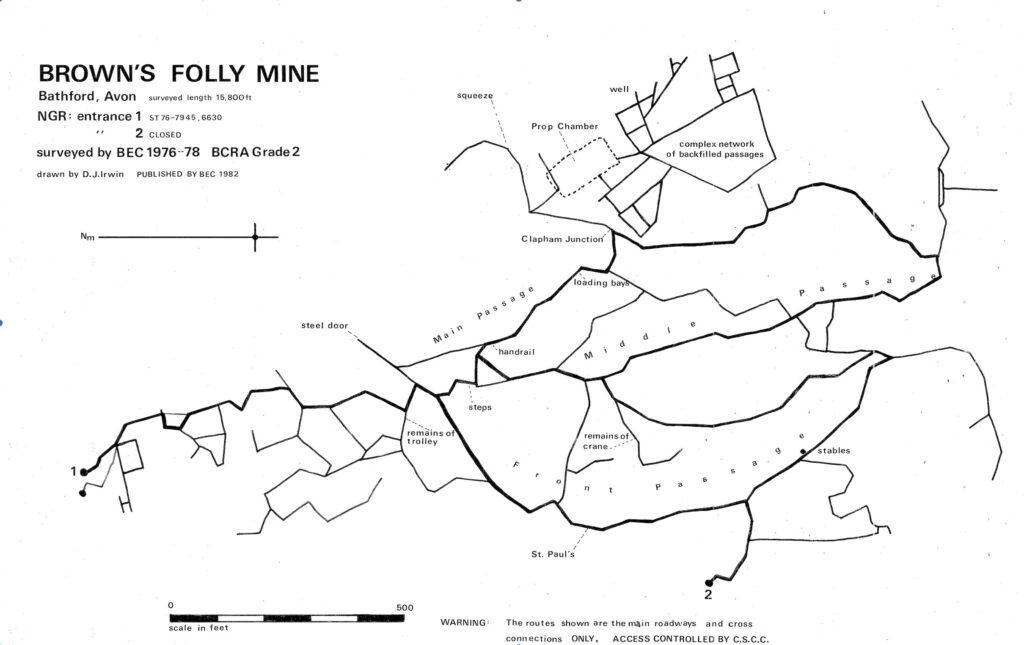

A slightly outdated survey of the system, showing the extent of the network. There are more detailed and more recent surveys available distributed by the Shepton Mallet Caving Club, it is not recommended to go into the system using this survey as a source of navigation.

The decayed remnants of a minecart within these passages provides a tangible connection to the mine’s industrious past. These robust vehicles, though often simple in design, were the workhorses of the underground operation, indispensable for moving materials through the labyrinthine tunnels. Their primary burden was the heavy, quarried stone, painstakingly transported from the working face towards the surface, but they also served to haul away waste rock and ferry tools or timber to the miners. The sight of such decayed remains serves as a poignant reminder of the daily human effort and the organized systems required to extract and transport stone in the demanding environment of these historic mines.

While not immediately apparent, pictured above are the remnants of the geared winch mechanism from a hand derrick system, once essential for quarry operations. This assembly, featuring a central winding drum and various interlocking gears, formed the primary lifting component of the derrick. Workers would operate it using hand cranks, and the gear system provided the crucial mechanical advantage needed to hoist and maneuver heavy blocks of stone. The rope or cable, coiling onto the drum, enabled the controlled raising and lowering of materials – a fundamental part of the extraction process in these historic quarries.

Far from simple relics, these stone basins discovered deep within the mine passages were crucial watering stations – horse troughs that tell a story of forgotten labour. In the dim, confined world of the historic quarry, they provided essential refreshment for the hardworking horses and ponies, the veritable engines of the subterranean transport system. These sturdy animals toiled daily, hauling immense loads of quarried stone or debris through the dark, winding tunnels. Strategically placed along busy haulage ways or near any rough-hewn underground stables, these troughs ensured the vital hydration of a workforce that literally powered the mine’s output. Seeing them now offers a direct glimpse into the era when animal strength was a cornerstone of the quarry’s demanding operations and logistical rhythm.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Browne’s Folly Mine embodies a dramatic journey through time, its once-bustling industrial heart now lays silent beneath the unassuming tranquility of a nature reserve. From its foundational role in quarrying the iconic Bath stone that shaped cities, through its strategic repurposing during wartime, the mine has undergone profound transformations and played an instrumental part in Bath’s history. Today, as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, its quiet surface and thriving wildlife mask the extensive network of tunnels below. Within these hidden depths, preserved remnants like timeworn tracks, miner graffiti, and decayed machinery offer potent, tangible links to the arduous human and animal labor of past centuries. Browne’s Folly thus stands as a compelling testament to Somerset’s rich quarrying heritage, illustrating a powerful narrative of industrial evolution, historical necessity, and the quiet reclaiming force of nature.