As part of a research project in collaboration with Queen’s University Belfast, select students in our school were given the opportunity to synthesise and analyse a novel protic room temperature ionic liquid (RTIL). The project’s goal was to first create the ionic liquid, triethylammonium hydrogen sulfate ([TEA][HSO₄]), and then demonstrate its viability as a greener catalyst for producing a biodegradable polyester, poly(ethylene succinate) (PES).

This article details the various processes our cohort undertook, from the initial synthesis of the ionic liquid to its final application in polymer chemistry.

Synthesis of the Protic Ionic Liquid ([TEA][HSO₄])

The journey to synthesise our target ionic liquid, triethylammonium hydrogen sulfate, commenced with meticulous attention to safety, operating entirely within a fume hood. First, triethylamine was placed into a small round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar. To manage the intense heat generated during the reaction, the flask was nestled into an ice bath.

The critical step involved the dropwise addition of concentrated sulfuric acid to the chilled, rapidly stirring triethylamine. This methodical introduction was paramount to control the vigorous exothermic reaction. Once the addition was complete, the mixture was stirred in the ice bath for a further hour to ensure the initial reaction proceeded safely.

Following this chilled phase, the ice bath was removed. The reaction flask was then allowed to stir overnight at ambient room temperature, driving the synthesis towards completion. The next day, the magnetic stirrer was retrieved, and the resultant viscous ionic liquid was carefully stoppered, labelled, and stored at room temperature, ready for use in subsequent catalytic studies without further purification.

Confirming Catalytic Viability: Qualitative Esterification Test

Before attempting to create a polymer, we needed to confirm our synthesised [TEA][HSO₄] could catalyse reactions. To determine if our RTIL was catalytically active we needed to devise an experiment that required a catalyst to lower the activation energy to a suffecient level to undergo reaction, while working within the constraints of the Graveney Science department. The experiment that we decided upon was an esterification of iso-amyl alcohol and ethanoic acid as it met the activation energy constraint and allowed us to diagnose the success of out experiment by using one of the most accurate pieces of equipment known to man - the nose. The human nose can be one of the most accurate and precise methods of chemical analysis often even outperforming specialised e-Noses (though not in ppm sensitivity). By using these highly precise “detectors” we had the confidence that we would be able to accurately measure the success of our reaction so therefore .

In our experiment, we prepared three test tubes. The first, a negative control, containing only the alcohol and acid and remained colorless with no notable scent. The second, a positive control, using concentrated sulfuric acid as the catalyst; it turned yellow and produced a strong, distinct pear drop smell which is exactly what we expected with the predicted ester isoamyl acetate. The third tube contained our synthesised [TEA][HSO₄]. It also turned yellow and emitted the characteristic pear drop aroma, confirming that our ionic liquid successfully catalysed the formation of new ester bonds. This demonstrated that our synthesised RTIL was indeed a catalyst and gave us the confidence to proceed to the synthesis of a polymer.

From Monomers to Polymer: Synthesising Poly(ethylene succinate) with [TEA][HSO₄]

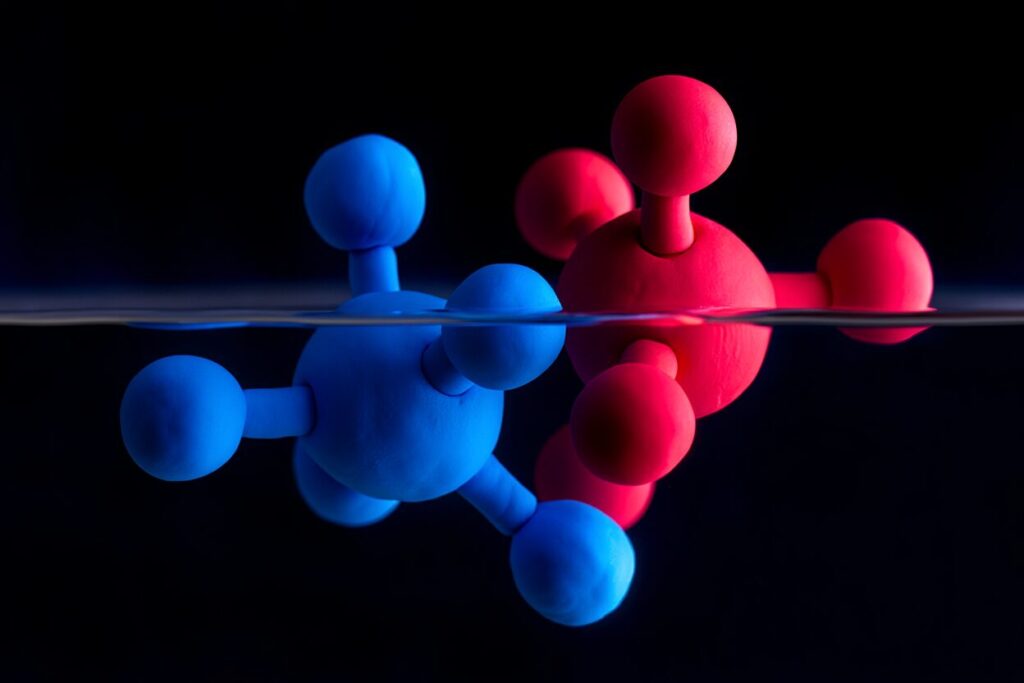

The ionic liquid that we would use for the polymerisation

Building on the successful catalytic test, we used our [TEA][HSO₄] to synthesise the biodegradable polymer poly(ethylene succinate) (PES). The monomers, succinic acid and ethane-1,2-diol, were combined with a catalytic amount (approx. 12 mol%) of our ionic liquid. The mixture was heated under reflux for one hour, during which all solids dissolved to form a clear, pale yellow, and slightly viscous liquid.

To encourage the formation of higher molecular weight polymer chains, the reaction was subjected to a second, longer reflux period. A drying tube containing silica gel was fitted to the condenser to remove water (a byproduct of the reaction) and drive the polymerisation forward. After four hours of this second reflux and subsequent cooling, a large amount of a flocculent white solid precipitated from the pale brown solution. This solid was the target poly(ethylene succinate), and its appearance confirmed that our RTIL had successfully facilitated the formation of long-chain polyester molecules.

Conclusion

This investigation successfully demonstrated a complete research cycle, from the synthesis of a novel catalyst to its practical application. We successfully created the protic ionic liquid [TEA][HSO₄] and confirmed its catalytic activity through a simple, qualitative esterification test. Subsequently, this RTIL was proven effective in synthesising the biodegradable polymer poly(ethylene succinate) from its constituent monomers.

The project highlights the potential of protic ionic liquids as viable, less corrosive, and greener alternatives to traditional acid catalysts like sulphuric acid. The hands-on process, from creating the catalyst to witnessing the precipitation of the final polymer product, provided vivid, memorable markers of reaction success and underscored the value of exploring these unique solvent-catalyst systems in the pursuit of more sustainable chemistry.